The Struggle for Human Rights in Latin America, 1967-2017

This groundbreaking exhibit focused on the struggles of various peoples of Latin America in the last fifty years, in order to shed light on the basic tenets of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. With original artwork and arresting objects from the U.S.-Mexico Border, Chilean prisons, and the jungles of Central America, as well as Latin American archaeological and geological artifacts, the exhibit focused on indigenous land and water rights, representation through cultural heritage, border migration, narco-trafficking, political movements and their suppression, and transitional democracy.

Drafted in the immediate aftermath of World War II, the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights represents one of several diverse initiatives by the United Nations to ensure lasting peace among nations at a fundamental or grassroots level. Called “a milestone document in the history of human rights” by the United Nations, it is the manifestation of the coming-together of representatives from different legal, cultural, and political backgrounds from all regions of the world to set basic standards for the ethical treatment of humans across the globe. Establishing that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights” and that all are “endowed with reason and conscience, and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood” and peace (UN 1948, Article I), the Universal Declaration ensures individual rights to life and freedom from slavery; political freedoms of association, conscience, and religion; and economic, social and cultural rights. It was subsequently enhanced by a variety of international covenants and protocols, most notably the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which further ensured rights of self-determination and subsistence. Collectively, they make up the International Bill of Human Rights which, by 1976, was entered into international law.

Latin America presents a compelling study of contemporary human rights. While internationally, several Latin American countries were leaders in the drafting of the Universal Declaration, domestically the same countries broke many of its tenets. This history of mistreatment and suppression of the most basic of human rights—as defined by the arguably Euro-American-centric Universal Declaration—can be traced at least to the period in which Europeans entered the continent (though of course the great precolonial empires saw their fair share of abuses as well). Indeed, the colonial period (c. 1500s) began the systematic erosion of indigenous autonomy that continues to this day. Corresponding to this, the exhibit begins with an examination of the ways in which indigenous people have been divested of their land, water, and even heritage claims; as a developing region, Latin America has capitalized on global demands for lumber, fresh water, and minerals—as well as intensified flows of tourism—with often detrimental effects on indigenous land, water and heritage claims. Economic and social imbalances stemming from the globalization of markets often compel the most marginalized into dangerous and often life-threatening labor situations, and the second part of this exhibit focuses on the diverse forms of migration that affect the bodily autonomy of these people—from human trafficking to indentured servitude to arduous border crossings in inhospitable lands. While the striking artifacts recovered from the desert at the US-Mexico border are inherently political the final section of the exhibit focused squarely on rights associated with the freedom of expression and assembly, paying close attention to dictatorships on the left and right, from Cuba to Chile, and their repression of the most basic of rights. Today, many countries continue to struggle with issues of justice, reconciliation, truth, remembering, and healing after years of oppressive military rule. Although these countries have a history of human rights violations, including military/police violence and involvement in extrajudicial killings, violence against and exploitation of minorities, and impunities for human rights violators, the last two decades of democratization have brought significant constitutional, legislative, and institutional changes in respect for civil liberties and the integrity of human dignity.

Disappearance was paramount in this exhibit, from the erasure of indigenous knowledge and identity to the literal disappearance of tens of thousands of political prisoners in Uruguay, Argentina and Chile. The imposing installation inspired by the notorious secret detention center in an old machine shop in Argentina asks visitors to contemplate their own presence, and their permanence in the memory of others; the spray-painted messages, memorializing ribbons and posters, and iconic silhouettes of The Disappeared reveal the peoples’ desire to never forget. Equally affective are the objects left behind by Mexican migrants—dirty, worn, abandoned—in decay. Whose objects are these? Why were they abandoned? What happened to their owners? We often don’t know. Yet volunteers meticulously comb the desert, in search of the lost and decomposing—sometimes turning these objects into inspired art—in an equally humane desire to never forget.

Focusing on Latin America—here used to denote all countries in the Americas except the United States and Canada (including Brazil and Belize, whose official languages are not Spanish but Portuguese and English, respectively)—runs the risk of conveying the erroneous notion that the English-speaking countries of North America are somehow morally above these human rights issues, or, at the least, are not implicated or embroiled in these particular struggles. In reality, the United States is neither immune to similar critiques of the historical repression of indigenous rights nor disentangled from the very conflicts represented here in this exhibit. Looking closely at the exhibit, we can find references to our common entanglement in these issues. For example, in the exhibit’s examination of indigenous claims to resources, we see that major global corporations—especially the Canadian-based Colombia Hardwood—are fueling Amazonian deforestation, complemented by the involvement of American companies like Monsanto and Dole in industrial, mono-cultural agriculture, such as the planting of vast groves of genetically modified soy and avocados. Our desires for iPhones, or for tourist objects, exacerbate these inequalities.

But quite possibly the most explicit references were found in the displays concerning human trafficking and in the installations on political rights. The latter present artifacts from dictatorships and bloody coups supported by the United States during the height of the Cold War—including U.S. military equipment from the secret wars in the Central American jungles made famous in the Iran-Contra Affair.

Finally, opposing sensations of freedom and despair were presented through the extensive display of artifacts from Mexican migrants recovered by American-based NGOs in the Sonoran desert outside of Tucson, Arizona. The installation of three bordados embroidered by members of Fuentes Rojas mark those who perished in the Mexican drug trade, which is largely dependent on North American demand, while the crosses and mixed media compositions by Alvaro Enciso—who uses entirely found objects left by migrants in the desert—remind us of the perils of migration and the troubling loss of life. Indeed, gazing at the sun-bleached objects carried from Mexico—some artistic and beautiful, such as the sketches by migrants on loose leaf paper, poetically written letters, or the stunning black-and-white calfskin bag; some mundane, dirty and worn, such as the broken telephone cards, soleless shoes, and weather-worn sweaters—not to mention documents such as Social Security Cards and U.S. prison records. While some of these artifacts were recovered near cadavers, the vast majority were simply found in the windswept desert, abandoned, and collected by Americans working for organizations such as Humane Borders, No More Deaths, or The Samaritans—who also regularly stock fresh water stations and raise money for migrant families We find hope amid the despair: hope in man’s humanity towards man; hope for nations’ adherence to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; and hope for a more equitable future through the awareness raised by endeavors such as this exhibit.

Exhibition Catalog Available

Mixed media artist Alvaro Enciso creates artwork out of found objects in the Sonoran desert to raise awareness of the plight of migrants on the militarized US-Mexico border. Sales also fund his Red Dot Project, in which he plants large versions of these crosses at the exact geographic locations that cadavers of migrants were found. You can visit him on Facebook.

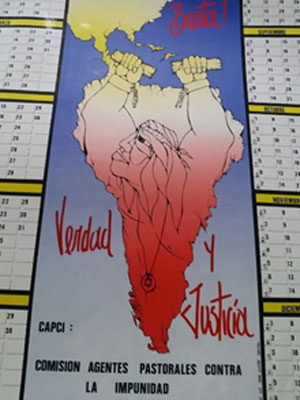

500 Years of Impunity, Enough! Truth and Justice. Pastoral Agents against Impunity. 1992 wall calendar advocating for indigenous peoples’ rights.

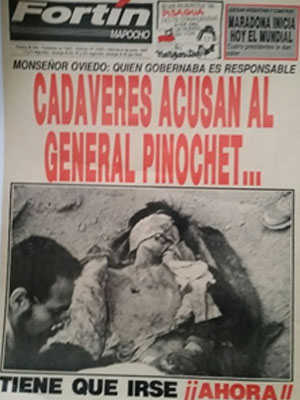

Front page of Fortin, Mapocho Newspaper. 8 June, 1990. “Monsignor Oviedo: Those Who Govern are Responsible: The Cadavers Accuse General Pinochet. He Must Go Now!” This blindfolded, tortured and then assassinated cadaver is offered as evidence against the crimes of the Pinochet regime.

Students Caitlin Seaman (left) and Genevieve Kull recreating graffiti on the installation, Remembering the Disappeared.

Cowhide bag, recovered in the Sonoran desert along with a makeshift stretcher. On loan from the Arizona History Museum

Photo Credit: Taria Rivera-Montes

Curator:

Michael A. Di Giovine

Student Co-Curators:

Heather Davis, Christopher Di Maria, Aaron Gallant, Amrita Ganguli, Aneesah Islam,

Ashley Jacobs, Jenna Laczkowski, Gabrielle Longreen, Emily Rodden and Caitlin Seaman

Faculty Consultants:

León Arredondo, Megan Corbin, Sebastián Guzmán, Daniela Johannes, Linda Stevenson